Under the theme “Connecting territories and adding struggles for good living”, the tenth edition of the Juruena Vivo Festival mobilized around 400 people in the Juruena River basin region. Between the 4th and 8th of November, guidelines related to territorial rights and environmental protection were discussed in the Nova Munduruku village, Indigenous Land (TI) Apiaká-Kayabi. A manifesto With the main referrals and demands, it was prepared and signed by the Juruena Vivo Network, a collective composed of indigenous peoples, family farmers, residents of municipalities in the region and civil society organizations.

“The network is this place of connections between the people who live here, who work and care about the life of the region. And the festivals are the big meetings, which we have called party and fight meetings. fight to ensure rights and face threats. And, at the same time, a moment to celebrate the beauties, diversity and advances. It is a story that started with five, six people, and now spreads throughout an entire region, because everyone perceives themselves in this common reality”.

Liliane Xavier, indigenist at Operation Native Amazon (OPAN)

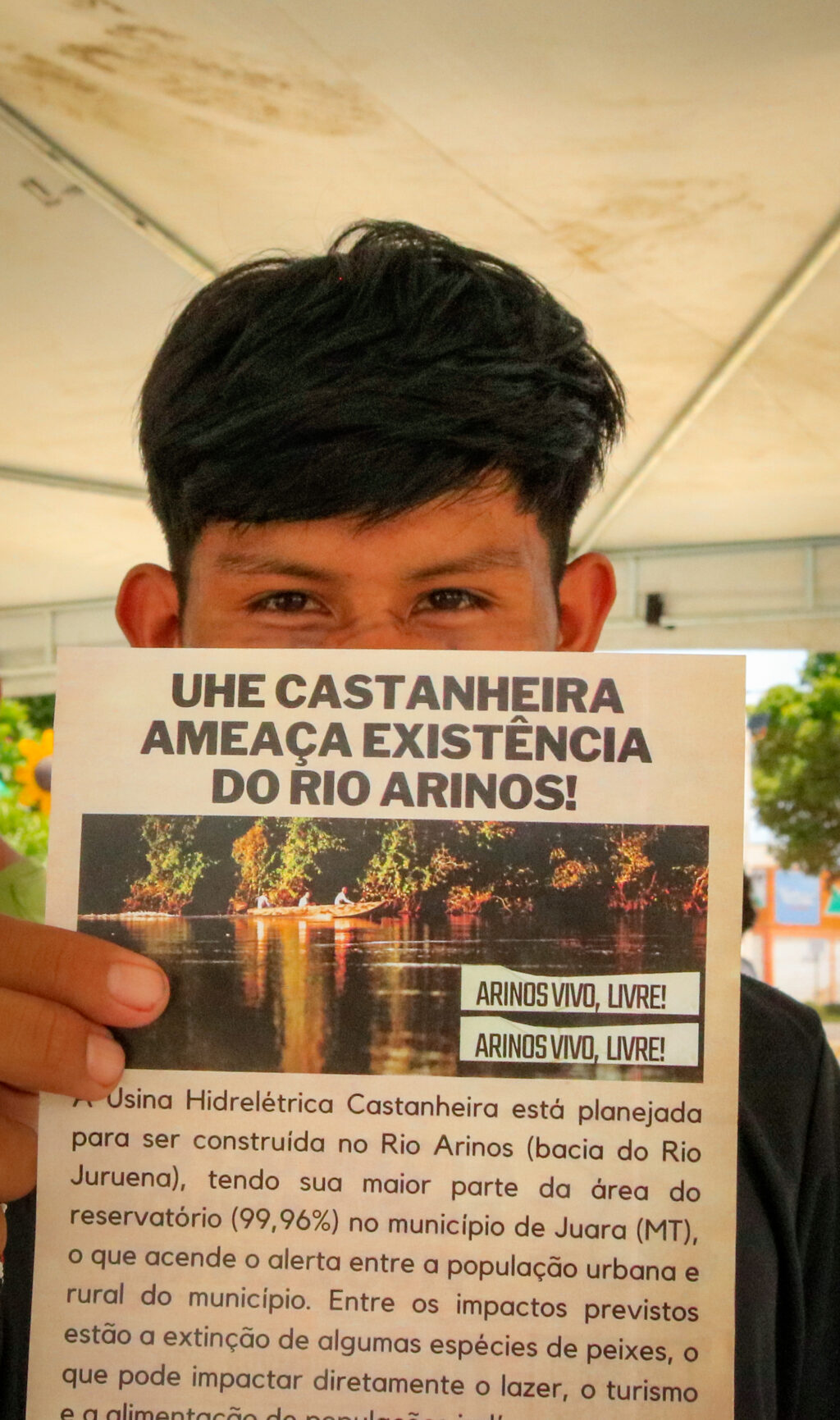

As part of the program, a march was carried out through the city of Juara (MT) against the project to install the hydroelectric plant (UHE) Castanheira. The manifesto letter was read and handed over to the president of the City Council of Aldermen, Sandy de Paula. The document will also be forwarded to the local City Hall, the Federal and State Public Ministry (MPF and MPE), the National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples (Funai) and the Federal Public Defender’s Office (DPU).

Through official documents, research and systematic surveys, OPAN and the Juruena Vivo Network maintain a constant work of monitoring threats and pressures, enabling greater autonomy and empowerment of populations. “Before, we only learned[do empreendimento]when the public hearing was already scheduled or when the entrepreneur was knocking at the door. Now, we gather this information and seek to share it widely. The strength of social mobilization and popular communication makes a difference. Communities start to create their own narratives”, adds Liliane Xavier.

hydroelectric projects

The Juruena River Basin, located in the northwest of Mato Grosso, is the most extensive in the state, draining more than 19 million hectares in an area that covers 29 municipalities. The basin concentrates 23 territories of more than a dozen indigenous peoples. In the region, pressures come from several fronts, such as agribusiness and mining. added to the hydroelectric sector projects, has been doing a true subdivision of the Juruena basin rivers.

The UHE Castanheira is pointed out as the main threat. Predicted to be built in the Arinos, a river known for its abundance of fish, the dam could alter the course of the water, compromising the reproduction of fish and other animals, such as a bivalve mollusk called tutãra By the Rikbaktsa. Its shell is the main element of a sophisticated necklace used by women during wedding ceremonies. The fragile and rare mollusk can only be collected by the indigenous people in the waters of the Arinos.

“We demonstrated against the hydroelectric projects in the Juruena basin, raised approximately 180 projects, with emphasis on the Castanheira HPP, Juruena HPP and Mato Grosso, presented as false solutions to the climate crisis and energy transition, but They destroy the life of our rivers and jeopardize the food sovereignty and cultural reproduction of peoples”, emphasizes one of the excerpts from the manifesto.

In addition to the three large plants mentioned, the document also draws attention to the Huge amount of small hydropower plants (SHPs) and hydropower plants (CGHS), whose licensing processes are simplified and the cumulative and synergistic impacts are undersized. So many undertakings, added to the effects of climate change, resulted in the abrupt decrease in the supply of fish in many rivers in the basin.

fish shortage and “zero quota”

The scarcity of fish in the rivers was even one of the guidelines of the II Fisheries Meeting, one of the tables that made up the festival’s program, and which was attended by the Apiaká indigenous people responsible for monitoring fishing in the micro-basin of the Rio dos Peixes. The report of one of the participants, Piani Kayabi, moved those present. “This is very sad for me that I am young. The fish dying, the climate changing. And it’s not just in the rivers. Where it is planted, it is no longer being born, where it is born, it is dying”, he concluded with a choked voice.

Another agenda discussed during the 2nd Fishing Meeting was the Bill No. 1363/2023, known as “Zero Cota”, which prohibits for five years, without any scientific support, the transport, storage and commercialization of fish in all rivers of Mato Grosso. In practice, it makes fishing unfeasible and jeopardizes the livelihood of 16,000 fishermen, as if they were to blame for reducing the supply, exempting from any responsibility the hydroelectric projects that make it difficult to reproduce fish, the use of pesticides that contaminate rivers and groundwater, the silting of headwaters by herds of cattle, climate change, among other factors. “We express ourselves for the celerity of the action of unconstitutionality of the amendment of the Fisheries Law, in the name of guaranteeing subsistence and protecting the crops that depend on fishing throughout the state of Mato Grosso”, proclaims the manifesto letter on the issue.

Climate changes

The table “Perceptions and adaptations of peoples and communities to face the transformations of time” had the participation of Dineva Kayabi, Tipuici Manoki and Jaime Rikbaktsa. During the conversation, mediated by OPAN’s Andreia Fanzeres, participants shared experiences at the Conferences of the Parties (COPs) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), and at international events for policies on the ongoing climate emergency.

Dineva recalled that participation in international events is important for the world to hear and become aware of the situation of Brazilian indigenous peoples and the environmental context: “It is a moment of political and climatic incidence. A moment we have time and voice.”

In this sense, the Manifesto Letter considers that it is not just the role of indigenous peoples and traditional communities to curb the climate crisis. “We, forest people, are the ones who suffer the most from the impacts of climate change and the ones that most preserve biodiversity and forests. It is the role of the State to think about public policies that allow the autonomy of indigenous and traditional peoples in the fight against climate change”.

productive sustainability

The festival also reflected on sustainable production models that enable income generation allied to the protection of the environment. The table “Experiences in the production and commercialization of family and indigenous agriculture” made it possible to exchanges between family farmers and indigenous people in the region. Renato Felito, from the movement affected by dams (MAB), spoke about the agroforestry experience in cooperatives of small producers and detailed the step by step for a possible change. “If production, commercialization, research and access to credit are thought of in a collective way, then we are talking about agroecological transition”, he added.

The importance of rethinking the logic of hegemonic production in Brazil, centered on monoculture, pesticides and capital accumulation, guided the discussions. “This outdated form of an economic model generates conflicts and inequalities, and we will not let it degrade our territories. We want support in the production of our own economies that are based on the sharing of resources, not on the accumulation, and that respect our diversities of knowledge, cultures and modes of production”, emphasizes the manifesto.

Dona Helena Oliveira, a small producer from the Pedreira and Palmital community, stressed that access to information is also fundamental in this struggle. Before knowing the concepts of agroecology in an agricultural school in the region, she thought about deforesting and using pesticides on her property of three bushels. “People do the wrong thing not because they want to, it’s because they don’t have knowledge. As I changed, many people can change.”

popular communication

With regard to access to information, popular communication was also discussed. The Juruena Vivo Network has maintained a group of popular communicators since 2016, composed of indigenous and non-indigenous young people from the region. “The communication made at the bases is an instrument for the protection of the territories and dissemination of the cultures that are rich in the Juruena basin, being a powerful instrument of struggle within the movement”, highlights the Manifesto.

During the Youth Meeting, young people shared their trajectories and experiences related to communication, in addition to raising proposals for collective constructions to stimulate writing. The moment was a preparation for the Great Meeting of the Juruena Basin Youths, scheduled for 2024.

people’s right to free, prior and informed consultation

Consultation with indigenous peoples is the duty of the State when it comes to enterprises with the potential to affect the way of life of these populations, such as the installation of hydroelectric plants or road construction. However, it often does not occur or ignore the form advocated by Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO), to which Brazil is a signatory, and which provides for it to be done freely, priorly and informed .

Although it is the State’s obligation, consultations, when carried out, are usually conducted by the companies responsible for the enterprise, putting into question the suitability of the process. Tipuici Manoki reported how indigenous people are usually treated in these situations.

“They think that there are only rivers here, they forget that they have people. When evaluating the impacts of a hydroelectric plant, social impacts are not considered”.

tipupici manoki

The festival reflected on the importance of creating and implementing consultation protocols, which are instruments for each people to indicate their own decision-making rules in free, prior and informed consultation processes. “It is a tool to defend us from those who want to explore our territories without consulting us. It is a right for everyone to create the consultation protocol according to their culture”, commented Ivanete Krixi Munduruku. “We demand that, since the planning of any enterprise, the right to consultation is respected and that the positioning of the peoples of the basin is considered”, reinforces the manifesto letter.

Demarcation of the Tapayuna Territory

It is not today that the will of indigenous peoples is not usually taken into account when other interests are at stake. In the early 1970s, after two criminal poisonings and an influenza epidemic that nearly decimated them, the 41 Tapayuna survivors were taken from their home territory, located in the Juruena basin, between the Arinos and Blood Rivers, and taken reluctantly to the Indigenous Land of the Xingu (Tix), where they currently live.

The people demand the return to the traditional territory, which would be one of the most affected if the Castanheira HPP leaves the paper. During a cultural presentation at the festival, the Tapayuna group wielded a banner with the message:

“The struggle of the Kajkwakhratxi/Tapayuna for the return to their original territory. demarcation already!”.

The manifesto letter is also explicit on this issue:

“We demand the demarcation of indigenous lands, especially the Tapayuna Indigenous Land, a people forced to leave the traditional territory in the Juruena basin, which have the right to return and have guaranteed their original territory, threatened by extractive projects and the HPP chestnut tree”.

A decade of struggle and advances

In addition to discussions, mobilizations and claims, the tenth edition of the Juruena Vivo Festival also celebrated important achievements. “In this journey, we managed to stop the advancement of several of these death projects through the struggle, the development of our territorial monitoring with alert systems and popular communication. We have reached spaces to raise our agendas at a regional, national and international level”, emphasizes the document.

During this first decade of existence, the consolidation of a collective sense of unity must also be highlighted.

“This feeling, this regional identity that the rivers unite us and we are also Tapajós, Juruena, Rio dos Peixes, Rio Cravari, Sacre and so many other rivers that form this great region, this awareness of the hydrographic basin, that it is necessary to participate in the decisions that interfere in our lives.”

Liliane Xavier

During the program, those present were able to enjoy the fair of knowledge and flavors and cultural presentations of the peoples of the basin, in addition to enjoying and acquiring the diversity of their handicrafts. There was also a moment for the exchange of seeds, while the sports agenda moved the late afternoons. Last night, there was an indigenous cultural parade and a great popular dance.

Present at the festival were representatives of the Apiaká, Kajkwakhratxi Tapayuna, Enawene Nawe, Rikbaktsa, Nambikwara, Manoki, Myky, Hali, Paresi, Munduruku, Kawaiwete/Kayabi, Umutina Balatiné, Boe Bororo and Matipu, in addition to family farmers from various communities, represented by the Pedreira and Palmital Association, Association of Marketing Producers of Cotriguaçu, Cooperative of Agricultural Producers of the North Region of Mato Grosso (Coopervia) and the Landless Rural Workers Movement (MST).

civil society organizations and partners that make up the Juruena Vivo Network were also present, such as the Socio-environmental Popular Forum of Mato Grosso (Formed), collective design, movement of those affected by dams (MAB), Institute of Life Center, OPAN, Coordination of the Indigenous Organizations of the Brazilian Amazon (COIAB), Federation of Indigenous Peoples and Organizations of Mato Grosso (Fepoimt), National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples (FUNAI) and Missionary Indigenous Council (CIMI).